“They're not real. You get that, right? None of it is real. The critics aren't real. The customers aren't real. Because... *this* isn't real.”

The response that follows this honest statement is that of a superficially performative “Okay” from a Portland Chef named Derek (David Knell) who fully embodies the showmanship nature many restaurant owners/chefs display to customers who are wealthy enough to keep their business/reputation going or utterly dismantle it with a single review/recommendation. It’s a disgusting display of conformity as well as the denial of a reality Pig demonstrates in it’s deconstruction of the false societal norms and customs it’s protagonist Rob Feld (Nicolas Cage) rejected in favor of a more reclusively simple life, a life that didn’t cater to serving the whims of people who’s professional status he once defined himself by as a renowned chef.

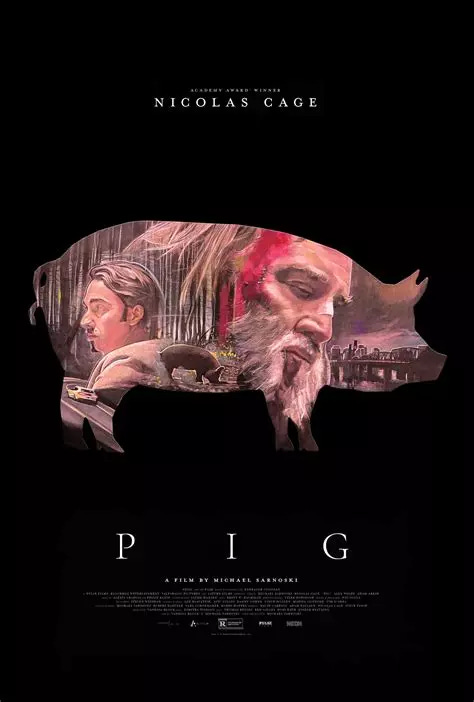

There’s a moment in the film, after Rob’s truffle scavenging pig is taken from him, that he’s told that he no longer exists. He is told this by a former colleague, whom he confronts about the whereabouts of his pig. Bizarre as the premise of this film centering around a man going on a path of revenge in pursuit of his pig, the honesty its storytelling conveys is one of clarity regarding the bigger picture of its setting. Upon first glance, Rob is shown to be filthy enough to be mistaken for just another homeless vagrant who embodies the essence of the homelessness crises reigning across the United States. He lives alone in a cabin deep in the Oregon forests, where he hunts for truffles with the help of his prized foraging pig. Rob sells the truffles exclusively to a young man named Amir (Alex Wolf). Amir is an inexperienced supplier of luxury ingredients to high-end restaurants, and like anyone lacking in experience, his insecurities are visible in their desire to reach the top of an industry that over sensationalizes the more artistic and cultured aspects at its center.

One of the more notable moments concerning Amir’s superficiality is in front of Rob and how he insists that the pig stay away from his fancy Camaro. He also dresses in high-end business attire, which are in great juxtaposition to that of Rob who could care less for his degenerate sense of fashion, or the societal status young men of Amir’s smart phone generation are conditioned to worship at the altar of, as if it had any true authenticity behind it as opposed to the many falsities that rob it of any true humanity. It is this same breed of cultural falsities that no doubt aided in driving Rob into becoming a recluse from a society that would gladly indulge in the sort of hollow emptiness that is clarified most in the scene Rob has with a Chef, who in that same scene is revealed to be a former student of his. As that scene plays out, it is revealed that when he fired him, Rob asked what he wanted to do. Instead of remembering his own desires at the time, it is Rob who reminds how he wanted to open a bar, a pub to be more precise. The more tragic part of about that scene is perfectly embodied by superficial professional politeness that David Knell’s performance conveys in his absolute denial of the reality of his situation, and how instead of being authentic, he chose a path that would only have his self-worth determined by the opinions of other people, which sadly is a commonality that has consumed the human being in a society that is governed by an overblown accumulation of wealth and a measure of status that can easily elevate or eradicate their sense of existence and how it functions in such a system, which has devolved to even more detrimentally destructive degrees regarding the attention economy we are all currently living under.

Whether its a figure like Andrew Tate pointing out that we live in an attention economy, or the notable times Joe Rogan has commented on how a majority of teens say that they want to be famous, or something of an influencer when they grow up as opposed to something more dignifying, it really illustrates how much culture and the idea self-worth has degraded. Knowing this truth makes Cage’s Rob Feld a remarkably honest character with a clear sense of perspective, unlike the other characters of the film who either chase superficial desires they have convinced themselves will bring them happiness or a sense of respect that is not real or constitutive of knowing one self. Aside from Amir chasing the false glory of status from the rich clientele his business with Rob ultimately aims to satisfy, his father Darius (Adam Arkin) keeps his comatose wife on life support, in spite of the unlikeliness that she will ever recover, all the while using the pig it is revealed he stole from Rob for his own personal profit.

Amir and Darious’ pursuits work in stark contrast to that of Rob, who in addition to not seeking out his pig for its alleged truffle seeking abilities, also had a wife. Throughout the course of the film, it is later revealed that following the death of Rob’s wife, his grief denied him the ability to continue his work as a chef, while at the same time granting him a sense of clarity as to the sheer hollowness that encompassed serving the type of high society people he would later chastise for their apathy and utter indifference they represent in relation to the passion that encompasses that nature of his work. This kind of realization is what brought him to the forest. It’s what brought him to finding a sense of solace with the very pig he willfully suffers to find. There are several moments in the film where layers of a seedy underbelly existing within the high-end cooking world, where chefs engage in a variety of illegal and morally questionable activities as opposed to simply embodying the falseness of the veil that society’s ignorance thrives on. It’s pretty much a call back to the comparisons that have been made with Pig and John Wick, which plenty of Youtube analysis videos have pointed out as a manner of deconstruction rather than simply direct comparison.

For anyone who loves the revenge aspect of John Wick, it’s more than understandable given that watching an innocent puppy or any kind of animal be subjected to suffering or vile mistreatment at the hands of unsympathetic human monsters is enough reason to make the idea of violent revenge similar to that of the Babayaga a more than noble crusade worth pursuing. But the nobility that paints the story of Pig isn’t about achieving any satisfaction from revenge or retribution. If anything, it’s about the acceptance of the pain and suffering that can often lead us to the sort of clarity where we recognize what is truly valuable in life, and how violence and hatred bring little if anything to its fulfillment.

It could be argued that in secluding himself from a hollow and superficially empty society, Rob freed himself. But because this came as a result of a great loss, there was still work to be done in confronting his pain, and this is fully captured when it is revealed that his precious pig died as a result of being mishandled by the faceless junkies Darius hired to capture it. This revelation in the story could be seen as a cheap attempt at invoking sympathy as a result of tragedy, especially when the cruelty visited on Rob and his pig gave enough reason to validate a craving for justice through sheer vengeance. But again, although Pig is structured as a revenge story, instead it illustrates the sheer pointlessness revenge would bring. As much as the death of Rob’s pig would serve as a reason for him to unleash the rage the film has clearly indicated residing within him, the choice to cook a wholesome home cooked meal as a means of brining out the humanity in a man as emotionally crippled as Darius, who had attempted to hold back his own grief, is further proof of how vengeance delivers little if any satisfaction, when love can produce an even greater result, even when given to those who have completely walled of their hearts to it, and allowed the more egotistically insecure part of themselves to dominate and define them. Darius is very much that character in the same ways that Rob is. Both had women in their lives that they deeply loved, and yet they supplemented their grief through different methods of escape. With Rob, he chose to welcome the company of a pig, much like how John Wick found solace in the kindness of a pup. But instead of ever listening to a tape his deceased wife made him, he chose to leave it, and this bares little difference to how Darius keeps his vegetable wife on life support, despite that zilch chance that she may survive, and despite how much Amir would prefer she be given the dignity of a merciful death.

It’s a painful experience to lose someone you love. It’s difficult to acknowledge the reality that comes from letting go, and Pig showcases how grief isn’t an easy thing to process, and our denial or unwillingness to face it can often cripple and even dehumanize us to a point where we either suppress our emotions to the point of becoming cold hearted monsters, or we supplement them with the superficially tolerable ones that most people often wear just to fit the standard society succeeded in making them accept, as if they were legitimate as opposed to antithetical to their overall humanity and sense of individuality.

The previously mentioned example of Rob’s former apprentice Derek is a perfect representation of this common behavioral pattern. After being reminded by Rob that he served under him for two months up until he fired him for over cooking the food, Derek immediately becomes defensive and even apologetic through his fake politeness, and the real nail on the head characterizing that moment comes from Rob who reminds him that around the time of his firing, he had told Rob that what he really wanted to do was open a pub. Sadly, that ambitious dream catered to something that was more commercially based, which not only illustrates the sheer hypocrisy that holds so much sway over people in the present day, but it also illustrates how in being dishonest with our own passions and failures, it can ultimately destroy us. Rob and Darius serve as severe representations of this given that the losses they’ve suffered and denied themselves the ability to confront for so long have involved people they’ve loved. In Derek’s case, it’s simply a sense of identity, which although not to the same extent of Rob and Darius’s traumas, it still involves a form of personal annihilation to one self, especially when centered around catering to the whims of people who don’t really care for him or any genuine passion fueling his work.

What we can take from a film like Pig is the complexity that comes with experiencing grief and the multitude of emotions that come from processing what is a very delicate emotional experience. Both John Wick and Pig tackle this through the approach of a revenge film, and although there is a sufficient amount of violence in Pig, most of it is dealt to Rob, at his own behest, almost like a form of inflicting punishment for his inability to confront the reality that came from losing his wife. It’s not your standard “Some really bad guys fucked with me, and so therefore I’m gonna fuck them up a hundred times over that the audience will have no choice but to cheer,” story. Delightful as the ending of the first John Wick is, and as much as any viewer with a soul can derive satisfaction from watching an unsympathetic character like Iosef Tarasov (Alfie Allen) die for murdering a puppy, Pig aims to empathize with the deeper emotional complexity that lies at the heart of the human being, be they good or evil. It could be argued that some of the lesser dimensional and screen-time grabbing characters within Pig are unsympathetic as a result of the cruelty and indifference their treatment of Rob showcases. But that is purely circumstantial. The more layered antagonistic forces like Darius, Amir, and Derek all embody an emptiness as a result of emotionally repressing that part of themselves that wishes to experience pain and the authenticity needed to stand against a world that is more focused on the commercial, the popular, and the socially acceptable rather than something sincere and riddled with the measure of kindness that Rob’s final act against Darius succeeds in crushing. It’s pretty much the perfect and nonhallmarky way of saying “Kill’m with kindness.” It’s not conventional within the context of a revenge film. But if there is anything to truly learn from Pig, is that too much convention can become the murder of one’s soul.

“If you're losing your soul and you know it, then you've still got a soul left to lose”

― Charles Bukowski

If You wish to support me and the work I do, then feel free to donate what you can. Even a dollar restores my faith in humanity.

Bitcoin

bc1qpyy3galr2z4wrm62t95dzme9kp9h00vje2gu6j

Monero

895uYBwiez7HQwawSyYtcwcNUqhugWXcAMaMgsTktgkoSyMQkKjjEU2duri5GfCi7AUSLHWyhSF76eRws5dfQGWZ42iyPSq

https://www.paypal.me/Vincentmurdock666

If You wish to support me and the work I do, then feel free to donate what you can. Even a dollar restores my faith in humanity.

Bitcoin

bc1qpyy3galr2z4wrm62t95dzme9kp9h00vje2gu6j

Monero

895uYBwiez7HQwawSyYtcwcNUqhugWXcAMaMgsTktgkoSyMQkKjjEU2duri5GfCi7AUSLHWyhSF76eRws5dfQGWZ42iyPSq

https://www.paypal.me/Vincentmurdock666

Affiliates

CashApp:

https://cash.app/$AndresIBenatar

https://cash.app/refer/P2DWNDH

ProtonVPN

https://pr.tn/ref/E8CMM7ETZZ9G

Swan Bitcoin

https://www.swanbitcoin.com/ViciousTheDevil

Fetch

https://referral.fetch.com/vvv3/referralsocial?code=3E1F4Y

Strike

https://invite.strike.me/IXEWYK

Ag1

Fold