The Crucible: Mass Psychosis, 17th. Century Wokeness, And The Importance Of Individual Identity vs. Modern-Day Cancel Culture

"Anyone who has the power to make you believe absurdities has the power to make you commit injustices.”

- Voltaire

“At its heart, wokeness is divisive, exclusionary, and hateful. It basically gives mean people a shield to be mean and cruel, armored in false virtue.”

― Elon Musk

“The further a society drifts from truth the more it will hate those who speak it.”

- George Orwell

If there is one thing the human race can often be credited for, aside from its propensity towards the least resistance, then it is its stride tribalistic impulse towards believing something that ranges from mad to outright bullshit. This tribalism often propels it to adopt a herd-like mentality that will abstain from either critical evaluation or the kind of deep self-reflection that allows for a society to truly look at the roots of its own problems as opposed to simply embracing a radicalized form of dogmatic hysteria masquerading as a virtuous form of puritanism. Arthur Miller’s play “The Crucible” as well as the film of the same name operates as a fictionalized account of the very hysteria that characterized the Salem Witch trials of the 17th Century, which accounted for the misguided accusation of over 200 people who were suspected of being witches. In the time of those trials, over thirty of these people were found guilty, while 19 were executed by hanging, all out of the fanatical belief of witchcraft and whatever supposed pact with the devil they were accused of making. Yeah, straight-up bullshit.

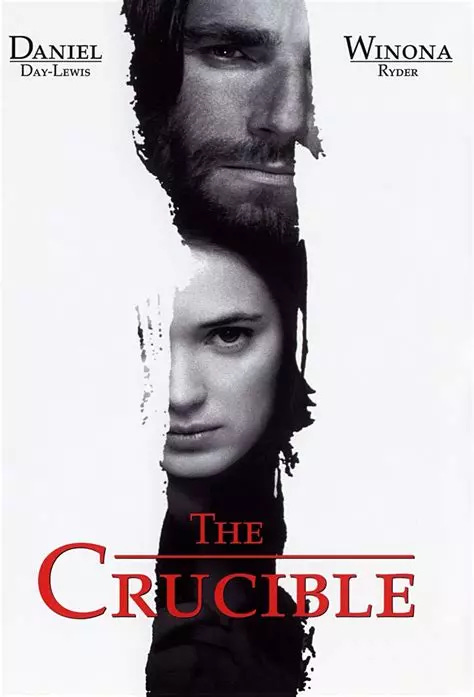

When it comes to a fictionalized account of a real-life event, it’s important to clarify the distinction while equally looking at the similarities that they share as a key point in determining the true significance that comes with garnering a true sense of understanding in what is blatant but an all too common form of the very tribalistic impulses that define much of humanity’s tendency and vulnerability towards mass psychosis. In the case of the real Salem Witch trials, the spark that ignited the fire of madness came from Joseph Glanvill a clergyman who claimed that he could prove the existence of witches and ghosts of the supernatural realm, despite having no credentials in science, which is ironic given that in modern times, many who claim themselves to be experts in certain fields be it science, Warfare, or even journalism (fake news) do so at the best of having not authentic certification too warrant the justification for whatever radical claims made. Now, the need for a license to showcase an essence of knowledge or wisdom does border on a great deal of absurdity. At the same time though, sticking your neck out and behaving as if you are the authority on a subject that actually carries a lot of weight and responsibility is itself a modicum of unfathomable consequences, which is something The Crucible explores through its fictionalized nightmare scenario of a world where God has truly died and the devil has taken on the form of a purity that works only as a form of personal profit for some while a form of malicious revenge for those with a more personally involved stake. That malicious vengeance comes in the form of Abigail Williams (Winona Ryder), a young girl who in her lust for her former master John Proctor (Daniel Day Lewis) concocts a plot to murder his wife Elizabeth (Joan Allen).

What starts out as a seemingly innocent exploration of Haitian ritualistic dancing turns into a hyper-exaggerated mass hysteria claiming that witchcraft is the real culprit and that the devil has descended on the very Salem that vows to abide by the same moral purity much of its crooked community claims to adhere to despite the notable examples of resentment and power-grabbing that goes on in the town. From accusations to outright false claims in an attempt to garner land, the marathon of accusations does nothing short of generate a culture of madness that hardly resembles an ounce of sanity or human dignity for that matter. If there’s anything that The Crucible manages to accomplish, aside from telling a great story dictating the inherent hypocrisy of 17th-century Puritanism, the film showcases something very Orwellian and how it very much resembles the modern phenomenon that is cancel culture, where not only had the dialogue of what we speak radically changed, but it has also gravitated to a level where once-respected figures are either condemned for expressing their views or forced to tiptoe around a particular demographic of subjects that have been ingrained with a majority-based form of sacredness that risks their reputations being desired or labeled as controversial all because of their contrarianism, which used to be merely an oppositional intellectual forefront as opposed to an unforgivable sin.

One key, if not monumentally modern example of this has been that of the Covid-19 pandemic, which just shy of three and a half years has changed the inherent direction of a world that has not only become more socially isolated, more echo-chamber centric, and more distrusting of centralized institutions—particularly in the medical and governmental level—that to even question the narrative is almost a form of repetitional suicide. Several key figures like Jordan Peterson, Joe Rogan, and Robert F Kennedy Jr. have faced social scrutiny for having views that work in opposition to the once-dominant narrative into the validity of the COVID-19 vaccine’s effectiveness. This measure of demonization has gone far enough to have them be labeled as either crazy conspiracy theorists or borderline dangerous, particularly in the context of the white-supremacist angle that has ensnared a culture that despite having more access to communication than ever before and yet is even more disconnected and to a point where it is susceptible to the types of hysteria that dampen their ability to think critically or discern actual disinformation—regardless of what experts claim—for the bullshit that it is.

The Crucible tackles this same pattern of misinformation through insanity of the witch hunt that grows from the barrage of accusations made by the same girls who claim to have multiple visits from a devil nobody else sees and yet in some ways has gripped the environment in which these early versions of what would be considered today’s social justice warriors to a point where to even make the wrong glance or make the wrong reference increases the risk being the object of mass demonization.

This pattern of mass psychosis is nothing new. All throughout human history, masses of humanity have been manipulated and willfully misled into believing carefully constructed narratives that either benefit the powerful or those seeking to acquire the kind of power that further supports or generates the evolution of these patterns of destructive fabrications, all the while allowing them to implement greater forms of social control. As to how people with greater levels of self-awareness navigate and essentially conquer these patterns, The Crucible gives no solution outside of the inherent awareness that several characters, notably John Proctor exemplify. The most incremental demonstration of this is from the famous “Because it is my name” scene where when he is given the chance to save his life and even the lives of other wrongly accused people through the act of making a simple false confession, Proctor rebelliously refrains from committing such spiritual perjury while stating “Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life! Because I lie and sign myself to lies! Because I am not worth the dust on the feet of them that hang! How may I live without my name? I have given you my soul; leave me my name,” which embodies both a courageous as well as an adamant opposition to the type of oppression that results from these trends of easily welcomed mass hysteria.

Although being left with his name and then executed, the willingness to embody such individuality in the face of oppressive majoritarianism is what makes The Crucible a notable piece of art to examine in a world that is currently working hard to regulate what is accepted as art or even acceptable speech under any cultural context at the risk of anyone with an alternative view to actually be honest. Whether it revolves around the subject of COVID-19, transgender issues, abortion, gun rights, or what classifies a particular gender, the fact that even having a civilized form of disagreement seems impossible only adds to the inherent sociological absurdities that gives the expression “May you live in interesting times” more flare than any fire anyone would like to play with.

The conflicts of today in comparison to the madness that paints the same Salem Witch Trials in which The Crucible dramatizes are mere representations of the times we live in and how they essentially push us to be better. One way that can be done is through a self-cultivated individuality that gives the John Proctor’s of Arthur Miller’s “The Crucible” all the much-needed humanity many so-called woke warriors or wokists (take your fucking pick) claim to embody in their fight for equity, transgender rights, and ironically free speech, even if that means ultimately silencing an opponent or even denying them the chance to argue their viewpoint.

“The deepest sin against the human mind is to believe things without evidence.”

-Aldous Huxley

https://substack.com/refer/andresbenatar

Affiliate Links Down Below

https://linktr.ee/viciouscormorant

https://substack.com/refer/andresbenatar

https://fountain.fm/show/eaalMjP1QIybelBMofNU

https://patreon.com/user?u=73393538&utm_medium=clipboard_copy&utm_source=copyLink&utm_campaign=creatorshare_creator&utm_content=join_link